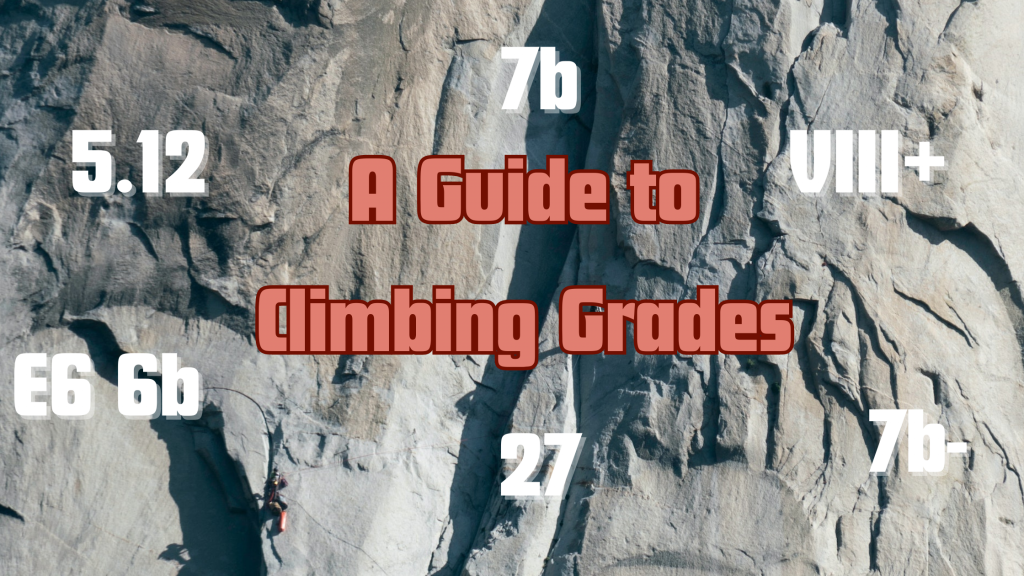

Climbing is a universal sport, spanning from remote walls in Alaska to the sunny sport climbing routes of Spain. But as the popularity of rock climbing burgeons globally, understanding the intricacies of climbing grades has become more confusing. This guide delves deep into the world of rock climbing grades, offering insights into their origins, variations, and how they compare internationally.

JUMP STRAIGHT TO OUR CONVERSION TABLE HERE.

Origins of Climbing Grades

The inception of climbing grades was fueled by the need to communicate the technical difficulty of a climb. As rock climbing areas proliferated and the sport gained momentum, a national climbing classification system sprouted in various regions, each tailored to the unique terrains and challenges they presented.

Navigating the Terrain of Free Climbing Grading Systems

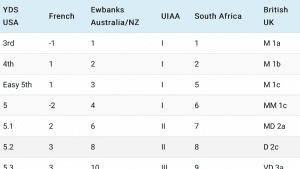

As rock climbing burgeoned across different terrains and nations, several rating systems emerged, each finely tuned to cater to its region’s distinct challenges mixed routes and climbs. Here’s a closer look at seven predominant systems for roped climbing and their introduction into the world of rock climbing:

Yosemite Decimal System

Yosemite Decimal System (YDS Grade): Born in the USA during the 1930s, this system, particularly its ‘fifth class’, is tailored for technical climbing. Grades initiate at 5.0 and advance with technical difficulty. The Yosemite Decimal System is the oldest climbing grade system still in use.

- Class 1 Hiking on a trail.

- Class 2 Simple scrambling, with the possibility of occasional use of the hands. Little potential danger is encountered.

- Class 3 Scrambling with increased exposure. Handholds are necessary. A rope could be carried. Falls could easily be fatal.

- Class 4 Simple climbing, possibly with exposure. A rope is often used. Falls may well be fatal.

- Class 5 Is considered technical roped free climbing; belaying is used for safety. Un-roped falls can result in severe injury or death. Class 5 has a range of sub-classes, ranging from 5.0 to 5.15dm to define progressively more difficult free moves.

British Trad Grade

British Trad Grade: Gaining traction in the 1950s in the UK, this dual-tiered system combines an adjectival grade (e.g., ‘HVS’) indicating overall difficulty with a technical grade (e.g., ‘5a’) spotlighting the toughest move. It’s holistic, encompassing factors such as dangerous fall potential and objective dangers. You may also hear people call it the British E-grade system.

French System

French System: Rising to popularity in the 1980s, this system has become the gold standard for sport climbing globally. It uses a combination of numbers and letters, e.g., ‘6a’, with ascending numbers denoting tougher grades.

Ewbank Grade

Ewbank Grade (Australian System): Introduced in Australia in the late 1960s by John Ewbank, this system, also adopted in South Africa, uses numbers starting from 1, with higher numbers indicating more challenging climbs.

South African

South African Climbing System: Emerged in South Africa as the standard for grading local rock climbing routes. This system is based on the Ewbank system with some variations. Gaining popularity in the late 20th century he South African system utilizes a straightforward numeric approach, starting from grade 1, which denotes very easy climbs, and progressing upwards with the increasing difficulty. Predominantly used for roped climbing routes within the country, its linear structure offers climbers a clear sense of progression in terms of technical challenge.

Yosemite Decimal System

First devised by the Sierra Nevada club in souther California.

British Trad Grade

This is timeline description. Please click here to change this The period after World War II, especially the 1950s and 1960s, saw a notable surge in interest.

Ewbank Grade (Australian System)

Ewbank developed the system as he felt that the grading systems in place at the time, especially the British system, didn’t adequately describe the climbs in Australia.

French System

The French climbing grade system, primarily used for sport climbing, originated in France in the 1970s. It gained popularity as sport climbing itself became more prominent.

This myriad of grading systems reflects rock climbing’s rich and varied history, showcasing how climbers have always sought to categorize climbs.

Tool for Climbing Grade Conversions

As rock climbing evolved and expanded globally, the multitude of grading systems that sprouted up in various regions began to present a challenge. Climbers traveling internationally often faced confusion when encountering unfamiliar grades. Hence the climbing conversion tool.

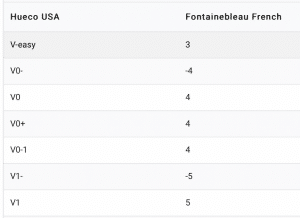

Bouldering Grades: The Bold and the Gritty

Bouldering compacts climbs into bursts of technical moves. Unlike roped climbing, bouldering concentrates the challenge into a limited number of moves, often demanding exceptional power, technique, and problem-solving skills. As climbers pushed the boundaries of what’s possible on bare rock, it became essential to have a grading system that reflects the differences in bouldering & other types of climbing. Given the sport’s global appeal, multiple grading systems have emerged, but two stand out.

V Scale

A product of American bouldering culture, the V Scale is predominant in the US and is becoming increasingly recognised internationally. Originating from the legendary bouldering locale of Hueco Tanks, Texas, this system spans from V0, signifying relatively easy problems, and has expanded to grade challenges as formidable as V17 and beyond. As bouldering continues to evolve, this scale is ever-adapting, accommodating the increasing difficulty of new-age boulder problems.

Font Scale

Named after the iconic bouldering areas of Fontainebleau, France, the Font Scale is widely embraced in Europe and numerous other rock climbing hotspots globally. The system’s intricacy lies in its split grades, starting as 3a, 3b, 3c, before progressing to 4a, 4b, and further. This fine-grained approach provides climbers with a precise gauge of the technical difficulty and physical demands they’re likely to encounter. As climbers traverse the forested regions of Fontainebleau, these grades become more than just a single number; they represent stories of perseverance, technique, and power.

Check out our Bouldering Grade Conversion Tool Here.

A Glimpse into Aid Climbing Grades

Aid climbing, a specialized facet of rock climbing, involves the climber leveraging gear placed in the rock (or existing fixed gear) to assist in their ascent, rather than relying solely on their physical prowess as in free climbing. As with all forms of climbing, aid climbing has its grading system, designed to give climbers an idea of the route’s complexity, the quality of placements available, and the potential risks involved.

- A Basic Overview: Aid climbing grades (or ‘aid grades’) range from A0 to A5. The ‘A’ stands for ‘Aid’, and the number that follows provides insight into the difficulty and potential danger of the route.

- Breaking Down the Grades:

- A0: Typically found on routes where aid is minimal, such as pulling on a piece of fixed gear or a bolt ladder. The safety is generally not in question.

- A1: Reliable gear placements abound, making progress relatively straightforward and falls safe, albeit potentially a bit jarring.

- A2: Slightly trickier. The gear might be more challenging to place, and there may be short sections where placements are suboptimal. Falls are still generally safe but might be longer than on A1 routes.

- A3: This is where things start getting serious. Long falls are possible due to placements that might not hold a fall. The climb is more strenuous and requires solid aid climbing techniques.

- A4: A serious challenge even for seasoned aid climbers. Gear placements are sparse and unreliable. While falls are frequent, they’re typically not life-threatening – but they can be harrowing.

- A5: The epitome of high-risk, high-reward aid climbing. An A5 route has stretches where no placements are deemed trustworthy, and a fall could be catastrophic, potentially resulting in a ground fall.

- Incorporating Clean Aid Grades: In an effort to minimize rock damage, “clean aid” (using gear that doesn’t harm the rock) has become more popular. Clean grades use a similar system but are denoted with a “C” (e.g., C0 to C5). The grades are roughly analogous to their “A” counterparts in terms of difficulty, but they specifically reference routes where hammerless tactics are employed.

In the world of aid climbing, it’s not just about physical strength or technical prowess. It’s about problem-solving on the fly, understanding the nuances of gear, and managing real risks. Whether you’re just venturing into the realm of aid climbing or you’re a seasoned veteran, understanding grades can provide valuable insights into what to expect on your vertical journey.

Commitment and Danger: Beyond Technical Grades

Beyond the mere technical maneuvers and sequences, the act of ascending a rock or mountain face can be deeply influenced by a myriad of external factors beyond technical difficulties. Some grading systems have recognized this multi-dimensional nature of climbing and have incorporated elements of overall grade that go beyond just the technical challenges. One prime example is the British Trad Grade.

- Understanding the Dual Nature of the British Trad Grade: The British Trad Grade is unique in its two-fold approach to grading. Firstly, there’s the ‘adjectival grade,’ which aims to capture the overall challenge of the route. This includes considerations like the quality and spacing of protection, the consistency of difficulty throughout the climb, and the exposure. Secondly, there’s the ‘technical grade’ that specifically hones in on the most technically demanding move or sequence on the route. By combining these two perspectives, the British Trad Grade provides climbers with a more holistic view of what to expect.

- Beyond Technicality – The Commitment Dimension: Some climbs demand more than just physical prowess or technical expertise. They require a deep-seated commitment – both in terms of time and psychological endurance. Factors that influence this commitment dimension include:

- Dangerous Route Potential: This takes into account the objective dangers on the route. It could be sections with loose rock, exposure to potential rockfall, or challenging weather conditions.

- Length and Duration of the Climb: Multi-day routes, especially those in remote walls climbed, inherently demand more from climbers. It’s not just about the climbing; it’s about survival, sustenance, and maintaining mental strength over extended periods.

- Remoteness and Isolation: The farther a route is from civilization, the higher the stakes. Retreat becomes more challenging, rescues are more complicated, and climbers must be self-reliant in terms of resources and decision-making.

- The Significance of Commitment Grades: Recognizing the commitment level of a route is crucial for adequate preparation. A climb might not be the most technically difficult on paper, but the added layers of endurance, exposure, and potential hazards can make it a much more formidable challenge. The commitment grade serves as a beacon, guiding climbers on what to expect and how to prepare.

FAQs

Conclusion

Climbing is a symphony of physical prowess and mental strength. Climbing grades grade systems, in all their variances, try to encapsulate this into a language that climbers worldwide can resonate with. Whether it’s understanding the nuances of the Yosemite Decimal System or decoding the Font Scale for that boulder problem, climbers are constantly adjusting this rich lexicon based on the era’s new challenges.